Boehme

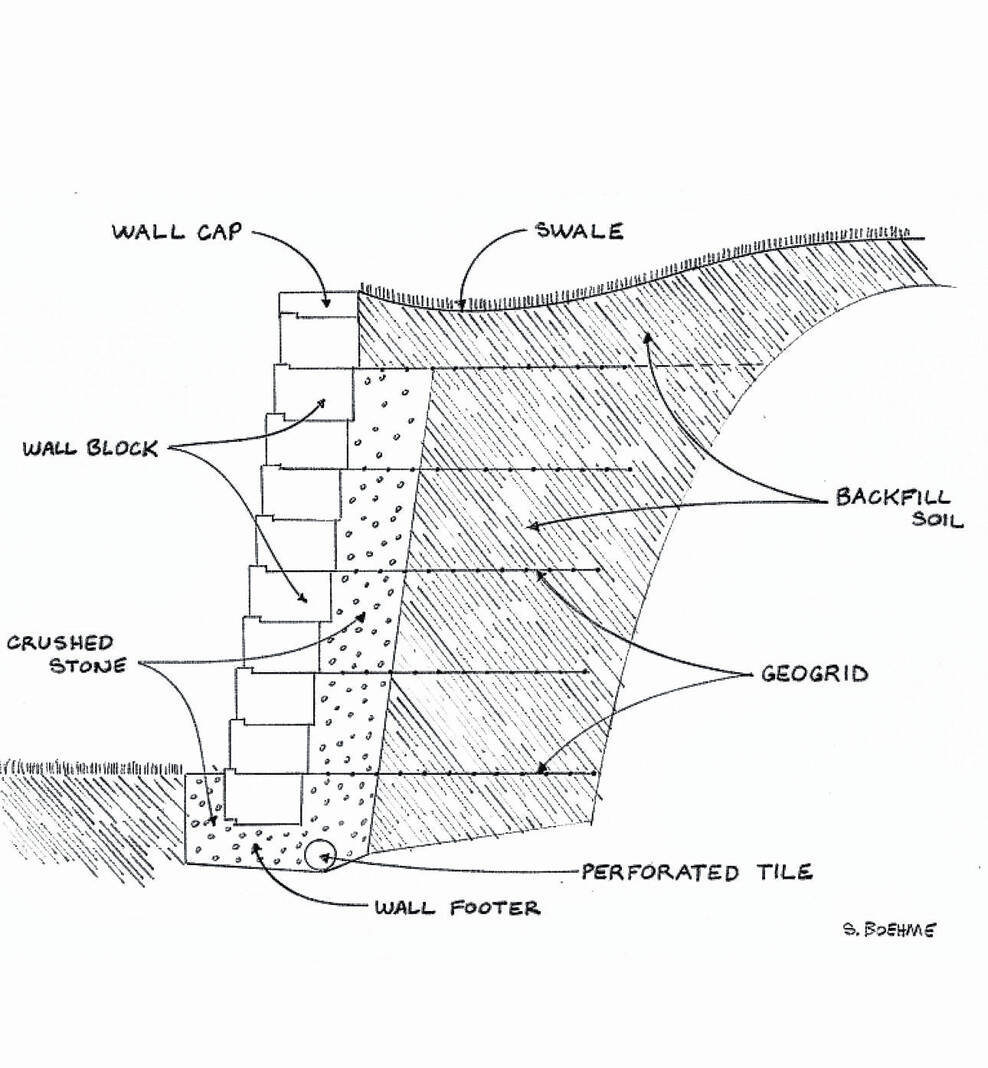

Retaining walls are more than just block; they include a footer, drainage, tieback and backfill. (Illustration by Steve Boehme)

Building decorative garden walls is very satisfying and rewarding, as well as being good exercise. We define “decorative” or “landscape” walls as wall less than two feet high. Retaining walls for purposes like holding back hills, supporting paving or buildings, and controlling runoff are more serious projects. Let’s call them “engineered walls”, because when the purpose of the wall is more functional, with long-term consequences, some basic engineering is essential.

Here’s a different way to think about a working retaining wall: think of the wall block as the “skin”, because a proper wall actually consists of four other important components. Let’s call these footer, drainage, tiebacks and backfill.

A wall footer starts with a trench at least twice as wide as the block depth from front to back. The bottom of the trench should drain like a bathtub, down to its lowest point, and not hold water anywhere. The footer trench should always be thoroughly compacted. The trench should be filled with layers of clean crushed stone, compacted in “lifts” of no more than four inches at a time. The taller (and heavier) the wall, the thicker this crushed stone footer should be. Since the bottom of the wall should extend underground, and good rule of thumb is to make the footer trench at least twice as deep as the thickness (height) of the wall block, and fill it half full with compacted crushed stone.

Backfill is the material behind the wall, between the block “skin” and the hillside you want to support. This should always be clean crushed (angular, not round) stone larger than one inch, to allow water behind the wall to percolate down. Backfilling with soil is a common mistake; wet soils expand and freeze, gradually pushing the wall over from behind. Soil backfill can also seep between the blocks and stain your wall.

Drainage behind the wall is key; improper management of water behind and under walls is the most common cause of wall collapse. Perforated tile at the bottom of the footer trench, draining to daylight downhill from the wall, should be installed before adding any gravel. Surface runoff from behind the wall should be diverted around it; ideally the wall should be tall enough to allow a drainage swale from end to end.

The wall block or skin needs to be “tied back” into the fill behind it. Typically this is done by installing a strong geotextile fabric, called geogrid, between the layers of block and extending back as far as possible into the backfill behind the wall. This netting is held in place by the weight of the block and the backfill gravel, forming a sort of sandwich. In order for the wall to fail, the geogrid netting would have to break, or pull out from under tons of gravel.

Understanding these basics is a good start, but there are many more tips and tricks that come with training and experience. Every wall situation is different, and there are many different types of segmental wall systems, each with cost-benefit tradeoffs. It’s important to know your own limitations before you begin.

As a certified hardscape contractor, we often get called after the fact when structural retaining walls fail for one reason or another. This is never a pleasant experience for us or the homeowner. It’s vastly more expensive and time-consuming to fix a poorly-installed retaining wall than to install it in the first place. Usually the cause of the wall failure is designed-in and the only solution is to remove it and start over.

Steve Boehme is a landscape designer/installer specializing in landscape “makeovers”. “Let’s Grow” is published weekly; column archives are online at www.goodseedfarm.com. For more information call GoodSeed Farm Landscapes at (937) 587-7021.